Yet the struggle between the regions continues; in fact very little has changed in the overall mentality of a lot Marnais – they still consider the Aube grapes and Champagnes as a lesser quality product. A big contributing factor here is the fact that there are no Grand Cru villages in the Aube (or any other department than the Marne for that matter). One of the reasons for this in my opinion is that the Echelle des Cru was first established and defined in 1927, when the Marne severely suffered in the aftermath of the First World War.

In this logic, one can possibly justify why the whole of the Cote des Bar (more than 6000 hectares of land) was uniformly qualified at 80% – the lowest level in the qualification system. One has to remember that the Échelle des Crus qualification system was originally established as a fixed pricing structure. The price the vineyard owner would get per kilogram of grapes was set depending on their vineyard’s village rating. Whilst some traditional champagne villages, such Ay or Ambonnay can probably rightfully claim their Grand Cru status – after all wine grapes have been produced here for centuries – the WW1 collateral can explain some of the ‘odder’ Grand Cru choices such as Sillery and Puisieulx. Following this reasoning, we can further explain why the Aube received one overall rating – they had been a lot less impacted by the war than the Marne.Having said this, nothing changed when the Echelle des Cru was reviewed in 1988 to be a better qualitative reference for the region: the Aube remained as it always had been at 80%. This once again reinforced the common believe that the grapes and champagnes from there were inferior to the one’s coming from the Marne… Again very odd if we take into account that the Aube is responsible for just under a quarter of the total Champagne production , and that most Brut Sans Année or NV Champagnes will have some Aube wines as part of the blend.

This begs to question what exactly defines the quality of a wine or Champagne. In Bordeaux the 1855 qualification was based on the price the bottle was sold at the time – eg the more expensive the wine the better its perceived quality. In Burgundy on the other hand the quality is very much linked to terroir – a notion which has become more and more popular in the wine world in the last few decades.

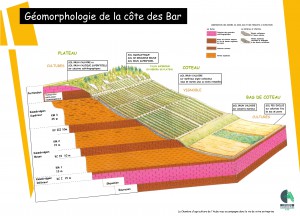

So if we follow the Burgundians and link the quality of the grapes to the terroir of a given vineyard or village as the Champenois claimed to have done in the Echelle des Crus, we need to find a definition for terroir. Most common definitions believe terroir encompasses the subsoil in combination with the micro climate, and exposure. If we apply this to Champagne and compare the two regions we can indeed see a difference between the Aube and the Marne – the subsoil in the Aube is limestone based whilst the Marne has a chalk based subsoil. For the rest the climate is more continental in the Aube, with slightly colder winters and warmer summers and the majority of the vineyards in both regions are often located on slopes and have multiple exposures…

Since the obvious difference is the subsoil, can we conclude that chalk is better than limestone to make Champagne? I find this a very dangerous assumption even if it is one the emerging English Sparkling wine community often refers to; after all they also have a chalk subsoil. Nevertheless very few experts really believe English Sparkling can pass for Champagne… It is just too different – chalk subsoil or not.Regular readers probably know that I find it very difficult to talk about terroir as in the subsoil, if we do not take into account the viticultural philosophy of the winemaker. This is because I believe there needs to be a possible exchange of the subsoil with the plant – either by having direct contact – eg deep roots into this soil, or indirectly by ground water exchange. There has to be some ways the subsoil’s minerals and nutrients are transferred to the plant and I believe that the systematic use of synthetic herbicides and fertilizers will hamper this direct or indirect subsoil exchange. Let me explain: systematic use of synthetic fertilizers discourages the plant to dig deeper for nutrients as everything it needs is readily available in the fertilized subsoil. Furthermore the use of herbicides and other synthetic products will fossilize the soil over time and the ground water exchange coming from the subsoil will be minimal if it is there at all – this has been shown in studies by soil experts Claude Bourguignon and Claude Kossura.

If we include this in the Champagne reality we can easily see why the different Aubois subsoil did not really matter, because traditionally the vineyards have been using a lot of fertilizer and chemical products. After all the Champenois yields are probably the highest ones in the world – which is quite a feat considering the continental climate.

However, as I wrote for Palate Press in April, things are changing in Champagne with the new Viticulture Durable en Champagne (VDC) policy. Whilst I personally believe that this policy does not stretch far enough, I also know that we cannot change decades of habits and ways of farming of more than 15,000 people overnight. So I see the VDC as an important steppingstone for change in more than one way and why not to eventually review the Echelles des Cru?

So lets get back to our original topic – the difference in subsoil between the Aube and the Marne – is there really a definable qualitative backbone to it? Here again we have to question what the subsoil can bring to the vine, grapes and wine to make it ‘better’ than the same vines (farmed in the same way) from another place. This brings us to minerality – yet another very difficult to define popular wine word. Sarah James Evans MW wrote a Decanter feature on the topic and started by saying that whilst she found the term useful, there is no definite definition on the topic. However, she elaborated “The wines being described as mineral are also generally described as ‘elegant’, ‘lean’, ‘pure’ and ‘acid’. They have a taste as if of licking wet stones and often a chalky texture to match.” She also added “The assumption is that mineral wines are superior to ‘mass market’ fruity wines“. However is there any proof that the champagnes from the Marne have a greater minerality then their Aube counterparts?If we ask geologist and pedologist Claude Kossura the answer is no. He explains this by making reference to the different historical ice ages which defined the formation of the soil structure. He points out that the soil structure in the Aube, just as Chablis, was formed after the second ice age. It is a layered structure which was formed in the Kimmeridgean and Portlandian age and consists mainly of clay and limestone. The clay can be more silt or marl based and just like the limestone it contains a wealth of freed mineral elements. The soil structure of the Marne dates back to third ice age, and is thus younger and different in consistency. The main elements are different chalk layers, some sand, limestone and sandy/silty clay. Again there are a lot of mineral elements present in this soil, however they are different from the ones in the soil from the second ice age.

Interestingly enough, Sarah James Evans actually makes reference to Chablis as a classical example of a mineral wine whilst she gives no example of a more chalky subsoil one. Even if I do not believe this means limestone and clay are more conductive then chalk to show minerality, it shows that some Aube terroirs are on par with the ones in the Marne, and could have Grand Cru status if we really look at the soil potential. I further subscribe to this after spending quite a bit of time visiting sustainable, organic and biodynamic producers in the Aube these last few months for my ‘terroir champagne’ book . Tasting their wines which – I like to stress here once again – all come from vineyards where the soil is extensively worked and viticultural practices are very respectful of the environment, I personally believe that the Aube’s terroir tends to give a great mineral note, especially in biodynamic champagnes. Excellent examples of more mineral champagnes are Vouette & Sorbee, Marie Courtin, Roland Piollot, Olivier Horiot, Fleury, Val Frisson, Ruppert Leroy, Jeanne de Rose, Coessens and Jacques Lassaigne. Most of them have a very flinty, smokey or wet stone characteristic which adds elegance and freshness to the cuvees.

I know I am not the only one who has noticed the great potential of the Aube champagnes – in the recent Organic Amphore competition, the Aube champagnes took the top spots. And several chef de caves have had me taste Aube Vin Clair whilst stressing the potential of these still wines are bringing to the blend – which means they have also noticed.

Nevertheless I do not believe the Echelle des Crus will change any time soon, more because of political reasons than anything else. However we never know, maybe when the Champagne appellation will be extended in a few years a full review of the terroirs will finally give the due credit to the Aube vineyards. In the mean time, I suggest you find a bottle of any of the producers I mentioned and that you make up your own mind :-) Santé !